Periodic signals have a high degree of autocorrelation, so the de-glitching hardware can usually find excellent splicing points. The H949 “de-glitcher,” and the de-glitching mode used in most time-domain pitch shifters that followed the H949, work well with signals that are as close to periodic as possible – i.e. If the ALG-3 has calculated the delay offset correctly, the 2 segments that are being crossfaded between will be almost identical, which will result in the least cancellations in the frequency and amplitude response. The H949 then calculates a delay offset, such that the new segment that is to be faded in is in phase alignment (or as close to phase alignment as possible) with the segment that is being faded out during the crossfade time. As described in an Eventide patent by Anthony Agnello, the ALG-3 board looks at the 2 delayed signals, and compares them to see where they share the most similarities – not just zero crossings, but true phase similarities.

The LU618 / ALG-3 board on the H949 works on eliminating this “glitch” artifact through a clever trick called autocorrelation. This can be heard as a “stuttering” artifact in the pitch shifted sound. Having the crossfading take place over a shorter interval helps to reduce the comb filtering, but results in an audible “glitch,” as the phase differences between the 2 read taps causes cancellations in the frequency response that is heard as a volume drop during the crossfading period. If the crossfading happens over too long of a time, the result is a metallic coloration of the sound, as the 2 read taps have a constant relative distance from each other that results in comb filtering.

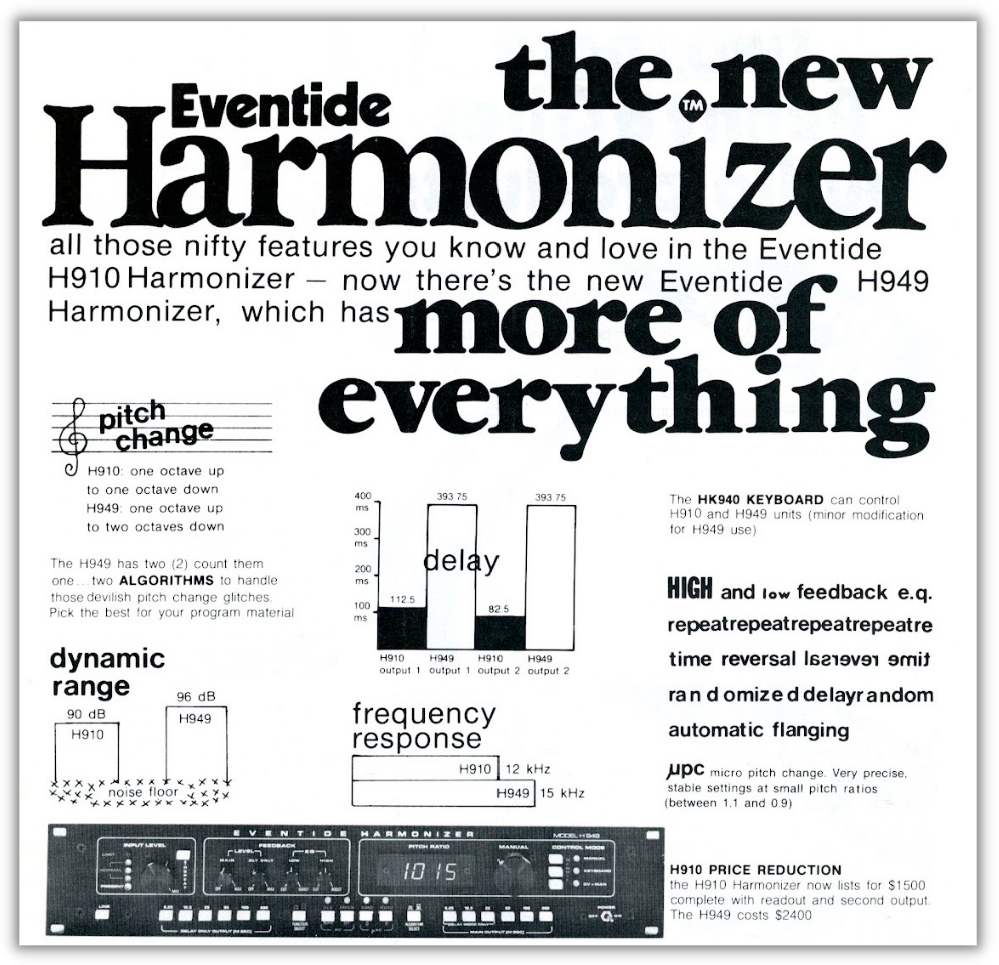

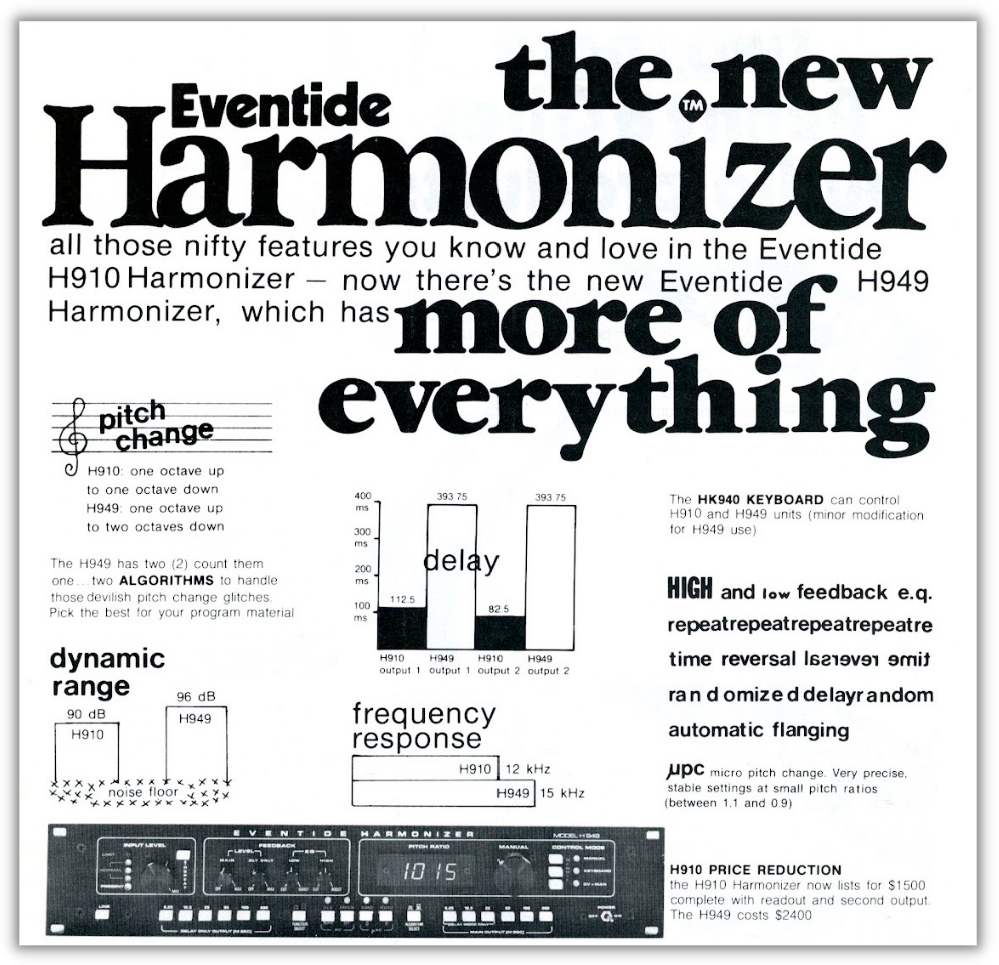

However, this crossfading is not without its problems. This is directly analogous to what happens in the rotary head tape pitch shifters, as a given read head rotates away from the tape. In a 2-tap pitch shifter like the H910 and H949, the volume change can be viewed as a crossfade between the 2 read taps. Pitch shifters deal with this artifact by fading the value of the read tap down to zero before making this jump, and then fading the volume back up again after the jump. Resetting the read tap to a different point avoids the issue of running out of memory or running into the write pointer, but this causes an audible popping sound as the read tap jumps instantaneously to some random point in the delay. In a modern delay line based around a circular buffer, if the read tap is moving through the buffer at a different rate than the write pointer, it will soon run into the write pointer, either by catching up to it or by being overtaken by it. Reading out of a delay line at a different rate than the data is written will quickly create a situation where the delay line runs out of samples to read. In the H910 and H949 pitch shift modes, information is being read into delay memory, and being read out at faster or slower rates, to change the pitch of the signal. However, from a DSP developer’s perspective, the most interesting feature was a new circuit board, the LU618 or “ALG-3” board, that was an option for earlier H949s and was added as a standard mode to later units.Ī somewhat technical review of the situation: The H949 built upon the harmonizing features of the H910, and added more memory (for longer delays), randomized delay, reversed delays, flanging, and a micropitch mode for small pitch shift intervals. The unique flanging, infamous reverse, time-altering delays, and distinct randomizing pitching effects made famous by the most groundbreaking artists of the last half-century, the H949 Harmonizer® plug-in is a door into a timeless world of creative musical effects mayhem.In 1977, Eventide released the H949 Harmonizer: The H949 also offered unique flange, reverse, and randomized pitching effects.Ī truly versatile tool for harmonic effects, double-tracking, otherworldly delays, glitching distortions and even very more extreme possibilities, the landmark combination of multi-effects in the H949 processor has forever changed the sonic landscape of music. Produced from 1979-1984, it introduced the MicroPitch effect, which used a proprietary single-sideband modulation technique for precise control of small pitch shifts.

Building on the legacy of the H910, the H949 was Eventide’s first de-glitched pitch-shifter. Artists could perform live and instantly create harmonies with unprecedented polyphony. It combined ‘de-glitched’ pitch change with delay and feedback.

Developed by Eventide in 1974, the H910 was the world’s first commercially available Harmonizer.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)